Céline Huyghebaert

Testimony

My conversation with Céline at Est-Nord-Est in February began with the observation that the stripped-down space of the studio that I was temporarily occupying made her feel good, because on the other side of the wall, the studio she had been living in for six weeks now looked very different. Seeking to give shape to her text, she had extracted it from the page and the screen. She printed it, cut it into pieces, spread it out on the wall and the floor. This way of doing things and occupying her space to write was certainly what most captivated the group with which I had gone to visit her studio the day before. I had to learn to detach myself, she told me, from the rigid image of the good writer sitting at her table. Yes: one must write with one’s whole body, all of one’s senses, we were reminded, not to lose ourselves in ethereal ideas. For me, in any case, this possibility of motion – just like the blank space of the residency, or of the page – is a kind of feminist permission that I must give myself. So, questioning the foundations of Céline’s approach is currently very appealing to me: what does it mean for an artist to be invisible or to appropriate her place?

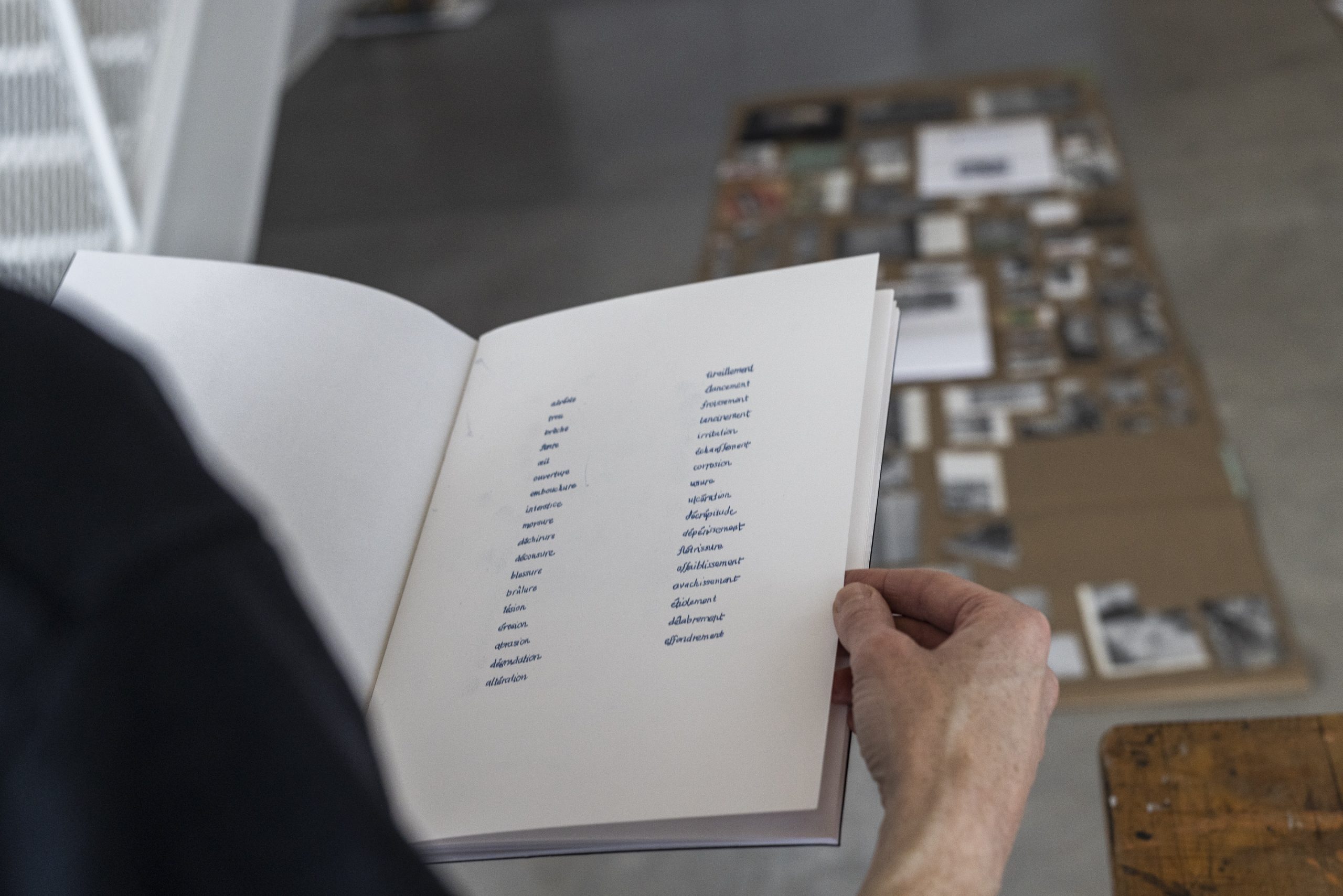

The book that the author Céline Huyguebaert is about to finish at Est-Nord-Est – a follow-up to her astoundingly successful Le drap blanc – is the completion of a research-creation cycle that she has built over more than six years. She started with two archival residencies (at La chambre blanche in 2016 and Artexte in 2018) in which she investigated which words are used in talking about art produced by women. She took notes on past exhibitions, read publications, photocopied exhibition leaflets and press releases, and so on. But, she told me, at a certain point, looking all the vocabulary lists she compiled, she realized that this kind of analysis could be conducted just as well, or even better, with software. What she was looking for, in fact, could not be. No: because, to understand the obstacles, doubts, and failures that are part of women artists’ experience, one would have to conserve a trace of what exists between the words. Céline therefore built her own archival collection with what she calls “ghost works,” asking artists to tell her about a work that they had never made. On the basis of these excavations, the cycle then developed into two exhibitions that presented letters from a fictional correspondence between Céline and an anonymous artist friend (Un cas particulier/A Specific Woman and Tes suppressions at, respectively, Occurrence in 2021 and Caravansérail in 2024).

Céline talks about her book project as if it were a quilt or a tapestry, a work that will be constructed on collective labour. And the burning question for me since the studio visit has been how, concretely, one manages to weave together all the voices as one writes alone. In fact, she told me, I think that right now I am hesitating between two projects, and the central distinction between them is that of determining the position to choose when faced with erasure: my own and that of the artists who answered me.

Can an artwork that never existed exist all the same? For women who feel invisible, the answer is often no, but doesn’t this mean simply that their nonexistence is a process of empowerment that makes them exist? As I am writing these lines, I don’t know which version of the book Céline has written – if she has been able to finish it, and when, and if she has doubts. But, like the image of her standing in front of her wall blackened by a beautiful storm, this book, which doesn’t exist (yet), nevertheless haunts me.

Biography

Céline Huyghebaert is a writer and artist. She works at the intersection of literature and visual art through prints, books, and exhibitions. She mainly uses poor materials and collaborative gestures to tell stories that are part documentary, part fiction. In 2019, she won the Governor General’s Award for her first novel, Le drap blanc, published by Le Quartanier, and was awarded the Claudine and Stephen Bronfman Fellowship in Contemporary Art.

Discover

Newsletter

Keep up to date with the latest news!